Blood on the Danube: Pride and Defeat at Nicopolis

This week in history, on September 25, 1396, the plains of the Danube ran red. What unfolded outside the fortress of Nicopolis was not merely a battle, but the death knell of the crusading spirit — a brutal reminder of what happens when pride, disunity, and reckless valor eclipse wisdom.

When word of the catastrophe spread across Europe, despair gripped the West. Chroniclers spoke of broken hearts, of Christendom struck by grief and shame. Later historians would see in this disaster the beginning of the end: nations turning inward, no longer united under cross and Christ, but divided by rising nationalism and bitter rivalries. The days of a united Christendom were over.

And yet — before the end came a spectacle of glory and gore.

The storm had gathered years earlier. Muslim Ottoman horsemen had poured into Hungary, burning, pillaging, enslaving. Its young king, Sigismund, desperate and outmatched, cried to Christendom for aid. The call was answered.

For once, fate seemed to favor the West. The long-feuding English and French had recently signed peace. Pilgrims and clerics returning from the East spoke of Christians ground under the heel of the Saracen, their pleas for deliverance fanning the flames. From every corner of Europe they came: French chevaliers, English long-sword men, Scottish lords, German and Spanish knights, Italians, Poles — a host unlike any before it.

Their ambition was boundless. As one contemporary put it, they dreamed of “reconquering the whole of Turkey, marching into Persia, Syria, and the Holy Land.” By midsummer of 1396, more than 100,000 crusaders gathered at Buda — the mightiest Christian host ever to confront Islam.

But numbers alone do not make unity. From the first campfires, jealousies and arrogance poisoned the crusade.

Sigismund urged caution. He knew the Turks, knew their cunning. Better to fortify and wait, he said. The French scoffed. They accused him of cowardice, of seeking to rob them of glory. They would march first, they declared, and take the laurels of victory for themselves.

Victories came easily at first. Two garrisons fell, and Nicopolis itself was soon under siege. When no word came of Bayezid, the French boasted that the sultan trembled before them.

But the “Thunderbolt of Islam” was already on the march.

True to his name, Bayezid struck like lightning.

While the crusader lords feasted in their tents, a herald burst in with chilling news: the sultan himself was near, his armies descending. Impetuous and proud, the French mounted at once. They did not wait for Sigismund’s Hungarians. They charged.

The first line of Ottoman cavalry broke before them — but it was a ruse. Hidden rows of sharpened stakes brought warhorses crashing down, impaling beasts and riders alike. Arrows blackened the sky.

Still the crusaders pressed forward, their heavy armor dragging them uphill under the merciless sun. The fighting was savage — axe and sword against scimitar and mace. Ten thousand Ottoman infantry fell, their lines broken. The crusaders hacked their way through, scattering the foe, cutting down thousands more as they fought their way to the enemy rear.

They believed victory was at hand.

Then, from the summit of the hill, the true host of Islam appeared.

Forty thousand sipahi cavalry crowned the ridge, their lances gleaming. In their midst, Bayezid the Thunderbolt raised his hand. The drums thundered. Trumpets blared. The hills shook with cries of “Allahu Akbar!”

The exhausted crusaders — armor-clad, parched, staggering — stood in shock. Then the wave broke upon them.

The clash was apocalyptic. Chroniclers wrote that no enraged wolf nor cornered boar ever fought more fiercely than the crusaders that day. Jean de Vienne, veteran of countless battles, raised the banner of the Virgin again and again. Six times it fell; six times he lifted it. Only when he himself was hacked down did it fall forever — his corpse later found with fingers still locked around the staff.

But valor could not stem the tide. Knights tumbled down the hill, others drowned in the Danube, still others fled into forests never to return. Sigismund escaped only by ship, lamenting, “If they had only believed me, we had forces in plenty to fight our enemies.” Even Froissart, chronicler of the French, admitted: “Pride was their downfall.”

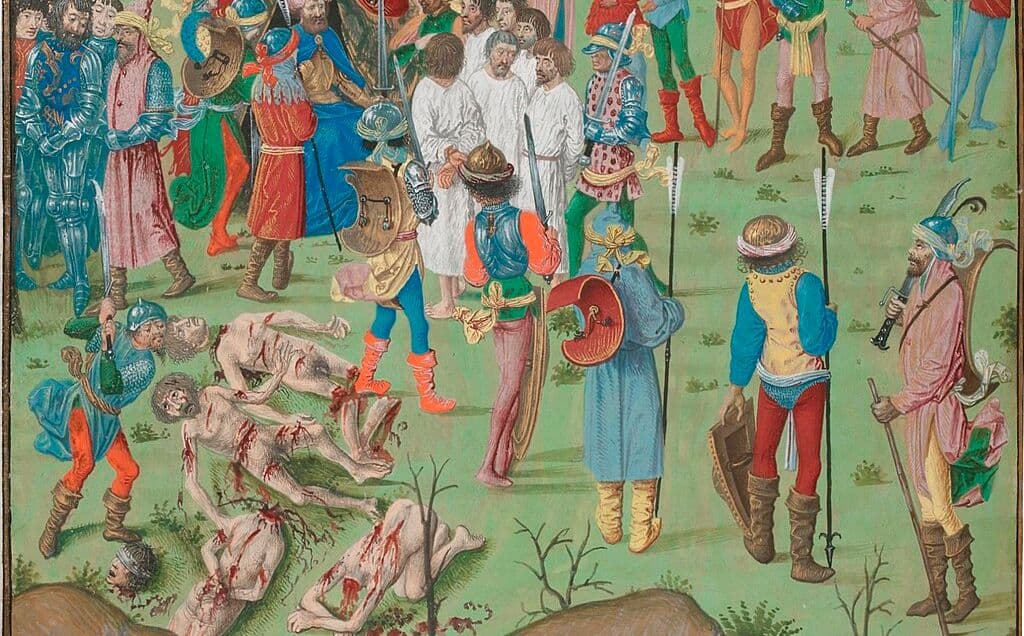

If the battlefield had been drenched in Christian blood, the morning after was worse. Survivors — thousands of them — were dragged before Bayezid. Stripped naked, their hands bound, they were given a choice: embrace Islam, or die.

Most chose death.

Hour after hour, heads fell beneath the sword, their bodies dragged away, their skulls stacked in grisly pyramids before the sultan. By some accounts, as many as ten thousand martyrs were executed before Bayezid, at last sated or disgusted, called a halt.

Nicopolis was not just a defeat. It was the twilight of the crusading dream. The crusaders had struck hard — one chronicler counted thirty Muslim corpses for every Christian slain — but victory was lost, and with it the hope of a united Christendom.

Never again would the West rally such a force to strike into the East. From that day forward, the defense of Christendom would fall only to its border states. The unity of faith that had once forged empires was shattered. In its place, kingdoms turned to their own ambitions, their own rivalries.

Nicopolis was a warning written in blood: when pride and division prevail, even the mightiest cause will fall.

And if that judgment was true in 1396 — how much truer is it today?

Raymond Ibrahim, author of Defenders of the West and Sword and Scimitar, is the Distinguished Senior Shillman Fellow at the Gatestone Institute and the Judith Rosen Friedman Fellow at the Middle East Forum.

Please share your thoughts on this article on X

Click here